Here is an excerpt of an essay I wrote for a Women’s Studies course on transnational cultural movements during my last year of college (2015/2016); I had a lot of fun researching the history of BL cultures in Japan and the West, and then interviewing self-identified BL fans I had connected with through my college anime club and FeministFujoshi. Here’s a dropbox link to the full essay! Enjoy, everyone.

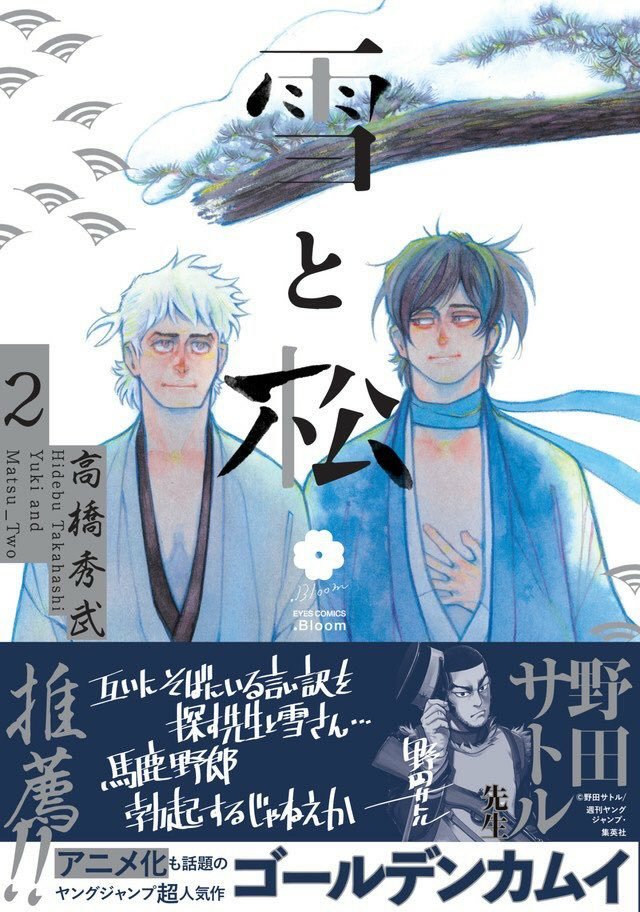

Fujoshi is a Japanese word meaning “rotten girl,” frequently used to describe female fans of yaoi: Japanese fanworks created primarily by women for women that depict men in same-gender intimate relationships (Galbraith, 2011, p. 212; McHarry, 2003). Both the terms yaoi and fujoshi first appeared in fan communities and have been (and often continue to be) used in playful self-mockery (McLelland, 2015, p.55, p. 169). Yaoi is also referred to as “Boys Love” although this term is more often used to refer to commercial products—most notably comics, but also novels, audio dramas, and games—rather than fanworks (McLelland, 2015, p. 5). For the sake of clarity, as well to highlight the fact that many fan artists go on to participate in the commercial BL industry and many artists within the industry still create fanworks (Lees, 2006), in this essay I will use “Boys Love” and its abbreviation “BL” as an umbrella term for both commercially-produced works and fan-produced works. Fujoshi represent not only a subculture, but almost inarguably a mainstream audience within Japan, with the BL industry grossing approximately 21.3 billion yen per year (Yano, 2010), and since the early-to-mid 2000s there have been an increasing amount of young people in the West becoming fans of this genre, creating thriving new subcultures. In this essay I will examine how these young people are reading and creating BL differently and similarly to the original Japanese fanbase—how they have transported and transformed this subculture.

[…]

While fan translations of From Eroica With Love, a 1979 shojo manga with (loosely defined) BL themes, circulated through amateur press associations in the US as early as the 1980s and the Aestheticism Boys Love fanzine began in 1996 with its companion website coming online the year after, events which suggest significant BL fan cultures were already developing, the first Yaoi-Con was not hosted until 2001, with the first BL original video animation, Kizuna, released on DVD the year after (Pagliassotti, 2015). Interestingly enough, Kizuna was released through Ariztical Entertainment’s Culture Q Connection line of LGBT films, with the company currently describing it as “the first gay male Anime [sic] to be released on DVD in the US” on their website (Aritzical, n.d.). This release of Kizuna as media specifically for gay men demonstrates how different cultural understandings of homosexuality in the US and Japan influenced the reception of this material in these different societies. Mark McHarry touches on this in his article “Yaoi: Redrawing Male Love” in which he quotes Mark McLelland saying that “The traditional understanding of homosexuality as a particular style or ‘Way’ of enjoying sex is still faintly discernible in certain media texts which speak of homosexuality as a ‘hobby’ [shumi] or a kind of ‘play’ [asobi/purei]” (as cited in McHarry 2003). Where Western understandings of homosexuality currently emphasize a largely fixed identity which is an intrinsic and integral part of the individual self, Japanese traditions of same-gender intimacy, such as nanshoku, or sexually intimate mentor relationships between adult men and adolescent boys, leave a lingering perspective which conceptualizes same-gender eroticism in terms of behavior and free-floating desire.

[…]

The racialized and gendered implications—as well as transnationality—of BL as a cultural phenomenon are evident even from its beginnings; Tomoko Aoyama, in her essay “Male Homosexuality as Treated by Japanese Women Writers” discusses how many female Japanese writers depicting same-gender intimacy in the 60s and 70s drew from Western influences, using Moto Hagio’s early manga “November Gymnasium” and its more developed manifestation, Heart of Thomas as one example of early BL manga’s frequent use of Western settings and characters, or Western influences when set in Japan (within the context of a wider body of Japanese literature written by women), and its purpose and effects. She writes, “The setting of a German gymnasium [in Heart of Thomas] works, because it is fictitious….The choice of young boys rather than young girls, and a German gymnasium rather than a Japanese school would appear to have been made…to avoid the ‘sticky’ restrictions of realism” (Aoyama, 1988, p. 188-189). Here, she emphasizes the additional distance that a Western setting and characters—in combination with the use of boys rather than girls in the narrative—creates between the story and its author and audience, thereby allowing for “free artistic expression,” (Aoyama, 1988, p. 189) for the author to explore different, often darker themes such as death, incest and more without being held back by the discomfort of personal vulnerability; because these comics did not depict Japanese women, they created a space for their authors, and arguably their readers as well, to explore issues that affected or interested them as Japanese women more confidently.

It also worked to create a kind of Occidentalism—reproducing an idea of “the West” that is unmarked, assumed to be coherent and stable. Toshio Miyake’s analysis of Axis Powers Hetalia, an amateur Japanese gag comic depicting nations anthropomorphized as young men provides a useful lens through which to look at the use of Western settings in early shounen’ai manga that Aoyama describes; Miyake discusses the way in which the overrepresentation of Euro-American nations in the text of Hetalia, as well as the popular character pairings in dojinishi, produce unquestioned representations of existing hierarchical geopolitical relationships, thereby reinforcing key logics of Occidentalism (Miyake, 2013, para. 4.3-4.6). Although Heart of Thomas and works like it do not literally represent anthropomorphized nation-states, their highly romantic, aesthetic depictions of setting and character that tie wealth, philosophy and romance to the West certainly carry occidental implications. Aoyama describes one novella, Koibito-tachi no mori (translated to Lovers’ Forest): “Though this story…is set in Japan, European flavor is apparent…characters are treated almost as part of the extremely gorgeous and occidental props” (Aoyama, 1988, 192). Although Lovers’ Forest was a novella that preceded early BL comics, and Aoyama states that there is no evidence of direct influence, the parallels between this and early BL works such as Heart of Thomas remain clear: use of Western settings, characters and philosophies that emphasize romanticism and intellectualism.

In a more modern context, there is still a clear emphasis on the romantic appeal and sexual dominance of the West in BL manga. Kazuhiko Nagaike’s article “Elegant Caucasians, Amorous Arabs, and Invisible Others: Signs and Images of Foreigners in Japanese BL Manga” examines representation of racial others, particularly White people and Arabs in monthly magazines that serialize BL manga; Nagaike discusses the racial implications of the large presence of White (or mixed-with-White) and Arab characters in BL, particularly the ways in which they are consistently portrayed as sexually dominant—as the seme in, to quote Miyake, “the boys’ love/yaoi code of seme (active, stronger, penetrating character) and uke (passive, weaker, receiving character) pairings” (Miyake, 2013, para. 4.5; Nagaike, 2009, para. 9). Nagaike argues that this parallels larger sociopolitical ideas regarding the feminine East in opposition to the masculine West, framing White characters as “superior others” in BL works (2009, para. 15-16). In contrast, Arab characters, also primarily represented as seme, are inscribed as “symbols of eroticism by means of Orientalistic images of harems and polygamy” (Nagaike 2009, para. 20), certainly masculine, but still depicted in a mysterious, largely unchanging and feminized vision of the Middle East. This reaffirmation of Western dominance and representations of Orientalist ideas of Arabs in BL texts (not to mention the conspicuous absence and negative depictions of non-Japanese Asian characters and Black characters) demonstrate women’s romantic fantasies’ complex entanglement with racism, something which is especially critical to examine in the context of BL’s globalization: as Western fans read their own fantasies and desires into works depicting Japanese women’s fantasies and desires, problematic racial dynamics are reinterpreted through a more globally dominant perspective, and this creates new points of fan engagement and complications surrounding representation and power in BL fan cultures.

[…]

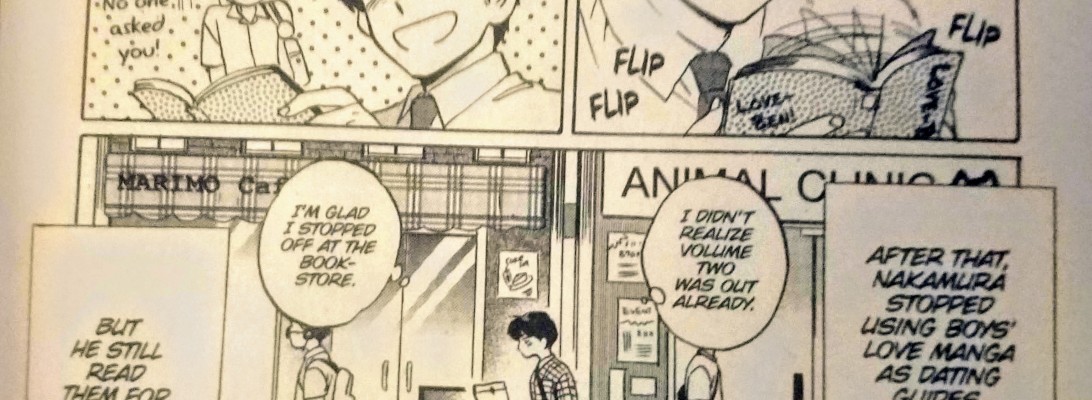

My own original research—personal interviews conducted over a period of approximately a week—also deals heavily with…transnationality and its implicit, part-and-parcel transformations of the source material….I found significant similarities to—as well as significant differences from—scholarship on BL fan culture both in Japan and the West, and will compare anecdotes and experiences related to me in these interviews to Patrick Galbraith’s essays “Fantasy Play and Transgressive Intimacy” and its slightly revised version, “Moe Talk” dealing with fujoshi culture and practices in Japan. I found Galbraith’s assertion that “How female fans of BL in Japan talk to one another…is not only pleasurable, but also productive of new ways of interacting with the world of everyday reality” (McLelland, 2015, p. 153) also very applicable to the BL fans I interviewed—one interviewee recounted to me a game she played with her friends very similar to Hachi, Tomo and Megumi’s “moebanashi,” or “moe talk,” sessions, which she termed “AU [alternate universe] where,” in which she created couplings or scenarios involving her friends—and, on occasion, strangers—playfully reimagining the world around her in terms of potential relationships and fantastic escapades which allowed her to engage with her everyday surroundings in new ways (A. Caliguiri, personal communication, March 13th 2015). However, one of my interviewees expressed a perspective directly counter to that of Tomo, Megumi and Hachi, stating that she did not identify as a fujoshi specifically because she associated it with “those girls who make everything into yaoi”—she went on to concede that she did occasionally find herself coupling characters from series that were not already BL, but stated that this only happened when there was a significant amount of subtext or connection between the characters, joking, “I don’t make everything into yaoi, I make yaoi into yaoi” (S. McKinney, personal communication, March 12 2015). The homosociality of BL fan culture was also apparent to me in my interviews—in the communication cited above, I spoke to two friends at once, and witnessed a great deal of physical affection between my correspondents. Additionally, toward the end of our time together we all began to exchange BL titles and authors we enjoyed, creating a kind of temporary and temporal intimacy through these texts reminiscent of Galbraith’s “surface intimacy” (Galbraith 2011, p. 214, 216; S. McKinney & E. Patel, personal communication, March 12 2015).

A few of my interviewees had actually experienced some degree of contact with Japanese fans, and frequently described the people they had encountered as more “mellow,” with one correspondent explaining, “Like you know how a lot of kids here go through a weeaboo [fanatic, often racist to some degree] phase thats [sic] more teenagers being obnoxious?? That didn’t really happen according to my [Japanese] friends” (S. Young, personal communication, March 8 2015). Another interviewee who had studied abroad in Japan expressed that an interest in BL was “less of a big deal” for Japanese fans, and that he felt interest in BL was more stigmatized in the US, with Japanese fans better understanding that BL fans could have other interests (M. Clogston, personal communication, March 14 2015). In contrast to this perspective, when I asked another interviewee if they had any contact with Japanese BL fandom, they related their experience of seeing the well-known Japanese cosplayer Reika at Yaoi-Con 2014, where, when she was asked if she knew any differences between Japanese and American BL fans, she said Japanese fans had vicious “ship wars” or fights over preferred yaoi couplings, and asked if that was common in America. The audience responded with a resounding affirmative and according to my correspondent, Reika replied, “well, I guess there’s no difference, then” (R. Wang, March 13 2015).

Marco Pellitteri discusses the spread of anime and manga throughout Europe, particularly Italy, writing, “I have recast the term [transculture] as transacculturation…to emphasize the process of cultural growth in a positive, or at least neutral, sense” (Pellitteri, 2011, p. 214). This process of transacculturation is happening with Boys Love media on a far larger, more global stage than ever before, with a growing body of scholarship exploring its many manifestations and implications, and fans exploring BL more and sometimes even in more conscious, complex ways. While researching I was overwhelmed by the amount of enthusiasm I was met with from fans of anime and manga and BL itself—nearly all the people I interviewed and several people I did not interview expressed a desire to read the finished version of this essay, and members of Davis Anime Club suggested I present on this topic at an upcoming anime convention. Transnational Boys Love fan cultures display complex negotiations of power, interpretation, and imagination that are always in play and always changing, but there are also incredible amounts of joy and excitement in these cultures: people are reconfiguring desire through politics of race and gender and nationality, people want to know more and more and more; like Hachi said of The Great Wave of Kanagawa reinterpreted through a yaoi lens: “‘This is so great! I never thought such a thing.’…Tomo commented that the person had gone ‘too far’…but this was delivered as a positive assessment, demonstrating well that play is the exultation of getting carried away” (Galbraith 2011, p. 226).