Finally getting around to posting a real review for this blog! Many thanks to cyanparade on twitter for bringing this book to my (and many others’) attention.

Stolen Heart was first published in 2002, with a story by Maki Kanamaru and art by Yukine Honami, and while it definitely bears many of the common shortcomings of the early 00s era of BL (and the genre as a whole), it does have its own distinct charm. The book includes 4 stories over the course of 6 chapters, the first three chapters being one story and the fourth a spin-off, while the last 2 are stand-alone; the story cyanparade referenced on Twitter is chapter 6, and–spoiler alert–it’s the highlight of the book.

Honami’s art is lovely, with excellent paneling that reads very fluidly and balances both the story’s romantic, atmospheric elements and its humor. I especially love the look of the first story, with its deep black tones and excellent depiction of motion!

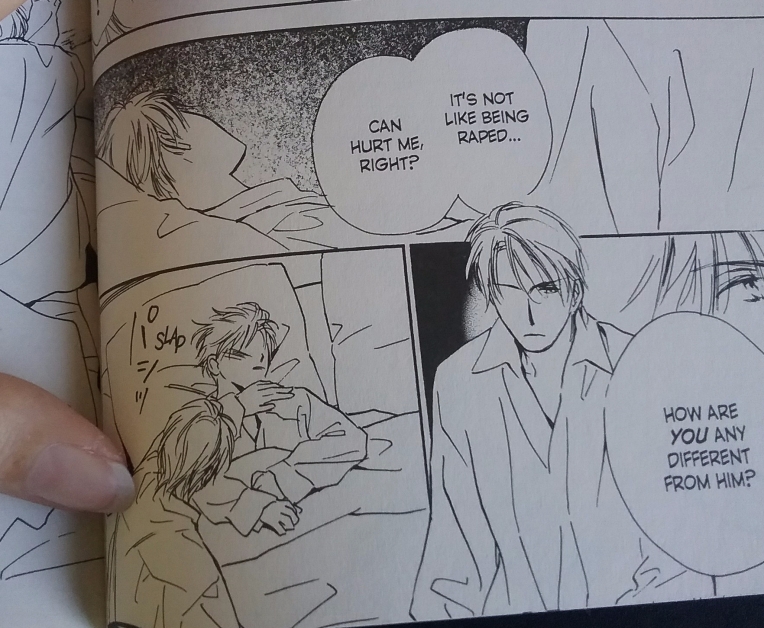

The characters are very likable, if somewhat archetypal–the ‘rougish thief who abides by his own moral code’ and ‘spoiled tsundere bocchan’ we meet in the book’s first story are endearing, but not well-developed enough to complicate any entrenched genre conventions–including, unfortunately, BL’s uh, difficult relationship with consent. This relationship is a particularly egregious example, with the thief repeatedly violating his partner’s boundaries, even beginning their relationship by drugging him in order to sleep with him. This behavior is even explicitly called out, only for the narrative to frame these protests as petulant and cruel.

Above, just to emphasize: bocchan brings up entirely reasonable parallels between his sexual assault at the hands of a stranger and his treatment at the hands of the thief and is subsequently slapped. His statement is framed as selfishly motivated and unnecessarily hurtful, acting out because he is lonely and insecure, rather than the completely correct and reasonable action it actually is, and he is punished for it by his partner and the narrative.

This is a horrible way to represent the consequences of sexual assault, and also makes it harder and harder to root for the couple as the story continues. The moments of genuine affection between them become incredibly frustrating, tainted by the complete disrespect and disregard the thief has shown for the boy he supposedly loves. It sucks, basically.

The ending of this story does raise some interesting questions regarding imperialism, monarchy, and the transfer of power; although bringing up imperial expansion from the perspective of the conquerors, even in a very romanticized and only pseudo-historical setting requires raises difficult questions that this chapter mostly ignores, I really do like the way the panels below touch on the impermanence of all political regimes. Additionally, the reveal that the kingdom in which this story is primarily set was originally stolen from the thief’s family further underwrites this conception of political power as inherently limited in and by time and space. It’s a nice bit of writing in an otherwise very, very messy story.

The next chapter, “Be Nice,” is a Cinderella reimagining with some uncomfortable possessiveness and class-based power dynamics–the protagonist’s love interest, who is also his master while he is a servant, coerces him into having sex with a couple of other nobles and then gets pissy and jealous when the protag complies with his explicit demand. The ending does soften the blow a bit, suggesting some narrative unreliability via the reveal that the thief has been telling this story all along (as if we needed more reasons to dislike this character!) It also features a gag panel with a BDSM-related subversion of the aforementioned class dynamic, which I found really fun.

It is worth mentioning that even though I tend to enjoy this flip of expected seme-uke dynamics, BDSM/kink cannot fix or compensate for an otherwise unhealthy relationship. Realistically, trying to do so will probably only make things worse, and I think it’s cruel to depict a relationship based on jealousy and coercion and then try to play off those elements of the established dynamic with a joke. Additionally, despite this reversal, the thief’s narration is not significantly problematized in the narrative–the ending may hint at more balance in the relationship, but the story we get is still the story we get, which makes this chapter a tough read.

It is worth mentioning that even though I tend to enjoy this flip of expected seme-uke dynamics, BDSM/kink cannot fix or compensate for an otherwise unhealthy relationship. Realistically, trying to do so will probably only make things worse, and I think it’s cruel to depict a relationship based on jealousy and coercion and then try to play off those elements of the established dynamic with a joke. Additionally, despite this reversal, the thief’s narration is not significantly problematized in the narrative–the ending may hint at more balance in the relationship, but the story we get is still the story we get, which makes this chapter a tough read.

The characters in “People Are What They Seem” border less on cliche than in Stolen Heart‘s first two stories, but I also found them less memorable. “People” is a high school story with a disorganized but earnest protagonist named Tomoyuki Naruse and Fujiyoshi, a bunny ears lawyer (er, student council president.) The relationship development between Naruse and Fujiyoshi feels rushed: Fujiyoshi ignores Naruse’s repeated requests to be left alone and Naruse demonstrates little reciprocal interest until he becomes suddenly hurt at finding Fujiyoshi in a seemingly compromising position with another student. There are also a few distateful jokes about sexual harrassment and one about incest–there is no actual incest, but Fujiyoshi and his brother are overly affectionate (in the vein of pet names and forehead kisses–it’s a little weird) and the narrative plays that ambiguity for some uncomfortable laughs.

The story does bring up some genuinely interesting questions, with Naruse declaring–title drop!–“people are what they seem” and arguing that how people choose to present themselves reflects on their character. This perspective is even validated by the narrative, with Fujiyoshi commenting that he “has a point.” However, these themes by and large go undeveloped; the narrative hints that ‘people are what they seem’ may not be a bad thing through Naruse’s burgeoning affection for Fujiyoshi, but after the climax where Naruse realizes his feelings for the prez, the story returns entirely to the status quo. The narrative fails to fully commit, instead repeatedly undercutting its own line of questioning with largely unfunny jokes. This left me dissatisfied, and is the primary reason I found this the weakest chapter in the volume.

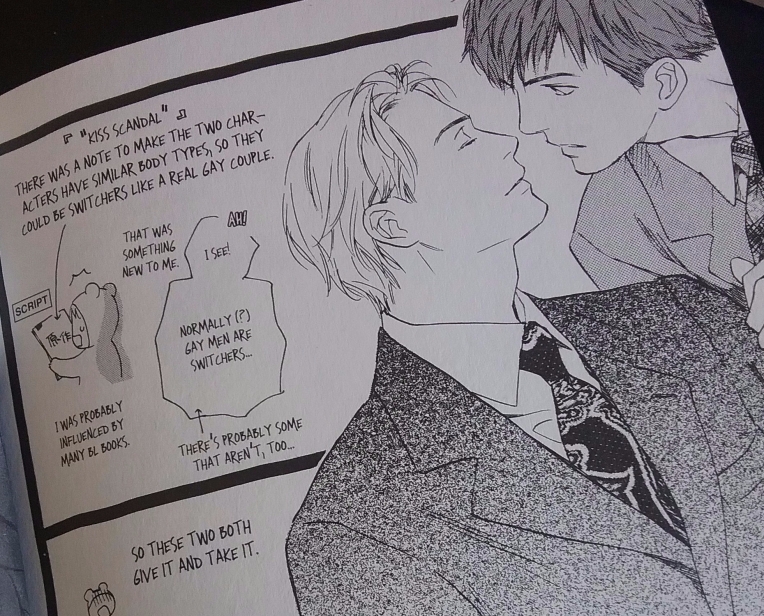

On a brighter note–finally!–the last story is my personal favorite, and I would argue the most feminist-friendly. “Kiss Scandal” revolves around Collin Rudd, a US Senator in a relationship with his secretary, Paul; when their relationship is exposed they are forced to deal with the personal and political consequences. It’s a short story that deals lightly with homophobia, and while it does border on sentimentality at times, I still found it really enjoyable. The two men are presented as intellectual and social equals despite one being in a typically subordinate position–plus switching!

I found this afterword super charming–it’s definitely embarrassing to be reminded first-hand that these stories are overwhelmingly written by women who have very little to no contact with actual gay people and gay culture/s, but I prefer it to heterosexual arrogance in telling stories about gay or bi characters. This is a reason, not an excuse–other people may feel differently, and that’s completely reasonable!

The chapter mostly focuses on Paul’s insecurities with regard to 1. Collin potentially leaving him to marry a woman and 2. (relatedly) standing in the way of Collin’s political career. This definitely edges toward unpleasant tropes given that it’s stated Collin is bisexual, but I think the narrative manages to avoid most potentially icky implications due to the specificity of Collin’s career and the fact that Collin makes it very clear he wants to marry Paul. Paul’s anxieties seem more reasonable and sympathetic given that Collin’s career does place him in the public eye and invite extra scrutiny on his relationships, and Collin’s readiness to commit dodges the gross biphobic stereotypes (unfaithful, basically straight, etc.) that usually accompany this sort of narrative in Western media.

Unfortunately, it still doesn’t quite manage to completely avert biphobic tropes–the narrative validates Collin’s guilt over ‘hiding’ or ‘lying’ about his sexuality by not being upfront with the media and his constituents about his relationship with Paul, and publically discussing his interest in women (implicitly, doing so without mentioning his interest in men.) This comes across as clumsy, failing to account for the ways in which coming out can pose very real dangers for LGBT people. It’s meant to demonstrate Collin’s honesty and integrity to the audience, and it does do that successfully! But it relies on common, unfair assumptions about how gay and bi people should navigate the world that lack nuance and understanding. >biphobia sp?

The story starts in media res, which helps Collin and Paul’s relationship feel very grounded as the audience is welcomed into the pre-existing familiarity between the two characters. One scene allows us to literally look at Collin through Paul’s eyes, as Paul’s internal monologue works with the visuals to establish not only love and attraction, but Paul’s genuine respect for Collin’s political ideals and ambitions. And even better, it’s made clear that this respect runs both ways when Collin suggests that Paul could run for office!

Obviously this is still very much a romance; Paul’s line about love taking precedence over dreams above is sweet, but definitely idealistic and sentimental. I think skewing more realistic in this genre is more a different kind of moe than trying to tell a story for gay/bi/queer people, but >value in women’s media/medium, and it’s still genuinely pleasant to read a romantic, mostly light-hearted story where the characters are equal partners who respect and admire each other. There are definitely other BL mangaka who are doing this and doing it well, especially in recent years, but it’s enough of a rarity that I’m excited and pleased every time I encounter it.

I like these characters and find their affection for each other satisfying and believable, and that’s never marred by rape jokes or disrespect played off as teasing the tsundere; that’s a pretty low bar, and it’s important to remember just how low it is, but these are tough times and I do try to count my blessings where I can!

Stolen Heart as a whole is a really mixed bag–it has solid visual storytelling as well as some genuinely interesting, thoughtful thematic beats, and the last chapter is a delight! But it also features multiple stories that misrepresent consent and sexual violence in deeply frustrating ways, which isn’t something that can be easily swept aside. If you can find it used or at a library (…unlikely, unfortunately) and none of the issues above are hard limits for you, it’s an enjoyable way to spend an hour or so, but it’s absolutely not something I would recommend to everyone.

Some titles I would recommend for BL fans who find some aspect of the story or storytelling appealing but are put off by the skeevy relationship dynamics:

- Heart o Nusumu no wa Dare da (Who Will Steal Your Heart) – a mostly low-key, romantic and sentimental story ft. a master thief

- Hashire! Ouji-sama (Run, Run, Prince!) – political intrigue with bonus democracy

- Rin! – also illustrated by Yukine Honami, with character growth and a sports story (archery) outside the central romance, very sweet! Available published by Juné, currently out of print but still available used for an affordable price.

I hope this post has been useful and/or entertaining for all of you–thank you so much for reading and for continuing to follow the blog!